Design Studio (Three) Three BA Architecture

Tutors: Constance Lau and Stephen Harty

Constance Lau practices and teaches architecture in London and Singapore. The studio’s research interests in multiple interpretations and narratives are explored through the techniques of montage as well as notions of allegory. Narrative as an ongoing dialogue in architectural design is further articulated through projects in the book Dialogical Designs (2016).

Stephen Harty is an architect and director of Harty and Harty.

Sweet Disorder and the Carefully Careless, Montage and the Picturesque

The arguments for cultural sustainability take onboard learning from history in order for existing knowledge to be preserved and adapted. These include social conditions that have evolved from political, economical and cultural shifts and in this instance have brought about new architectural typologies. The acquisition of plants during the eighteenth-and-nineteenth-centuries generated and established different ways to present, represent, discuss and engage with aspects of nature. These included the conception of greenhouses, museums and galleries that were exemplified in works of architecture in Kew Gardens, 1759 and the Natural History Museum, 1881.[1] Consequently this integration of education and entertainment was articulated through design strategies where the landscape and architectural features were co-dependent. The adherence to particular instructions and design approaches resulted in aesthetic pleasures referred to as the picturesque.

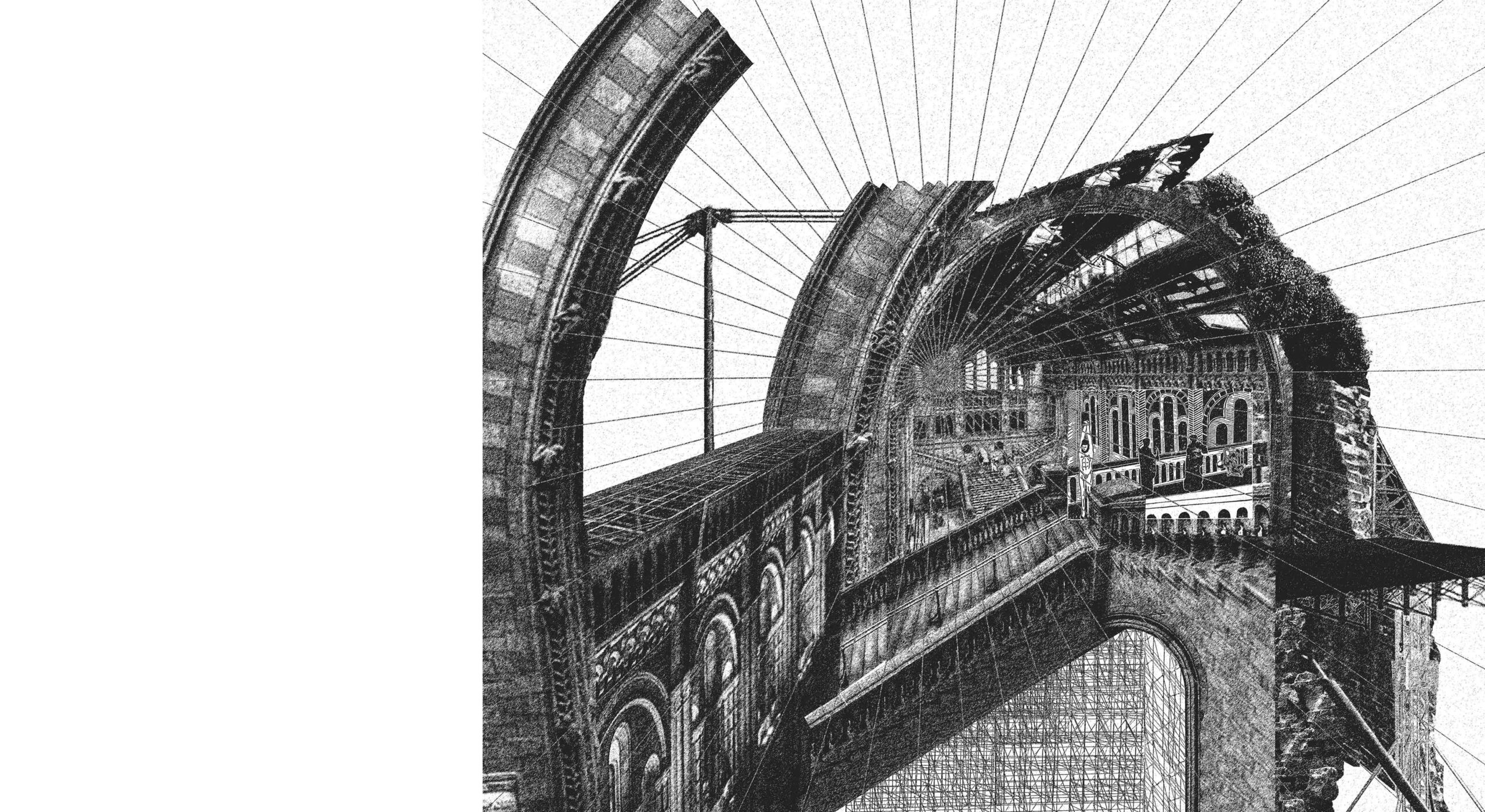

In the picturesque, the search for an idealised vision of nature spearheaded the argument that works of art can be appreciated solely for their objective qualities and hence irregular features like broken lines, irregular forms as well as the play of light and shade were important characteristics.[2] This expression of ‘carefully careless’ resulted in attempts to orchestrate nature through different framing techniques. In the practice of architecture this idea of discovering beauty solely created by nature was manifested through the construction of foregrounds, middlegrounds and backgrounds to enable a sequential montage composed of separate visual and tactile user experiences.[3] This notion of an architectural promenade by means of a narrative created through routes, viewpoints, architectural objects, and landscaping will be explored, updated and expanded upon in the work.[4] Hence the argument that the recording and recounting of history is not a liner process and all views expressed are interpretations of selected research material is important.

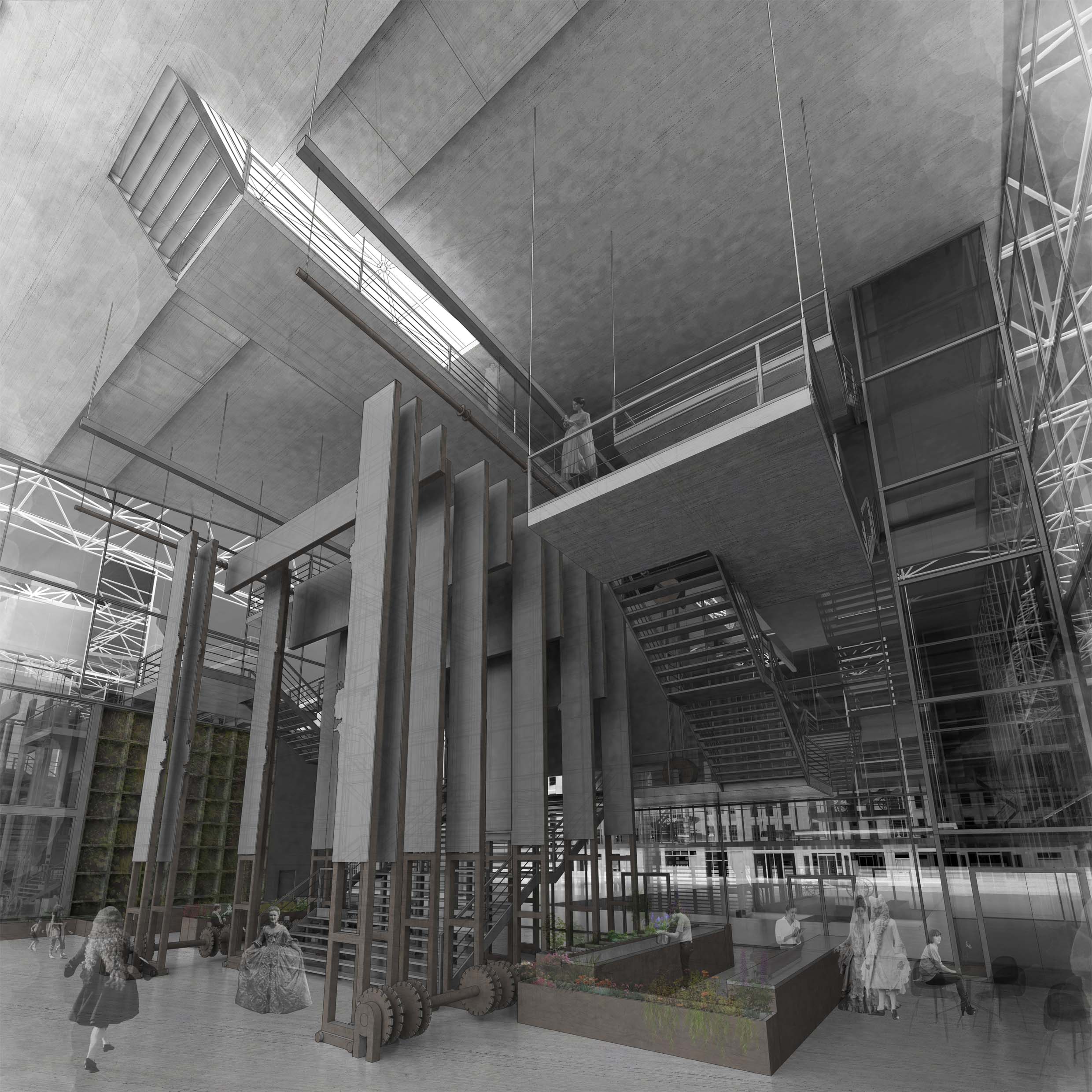

A montage of experiences

composed from fragments and entireties enables the creation of different user

interpretations. The techniques of montage as a spatial device in this instance

can also be regarded as the precursor to Bernard Tschumi’s development of the

architectural ‘stage-set’ to contain the collision of events, users, spaces and

movements in The Manhattan Transcripts (1981). Hence the idea of ‘sweet disorder and

the carefully careless’ concerns the layering and integration of ideas from the

picturesque and the urban strategies expounded in the Transcripts to generate different readings and meanings of nature

within the current context. These will form the key ideas for the ensuing design

proposals.

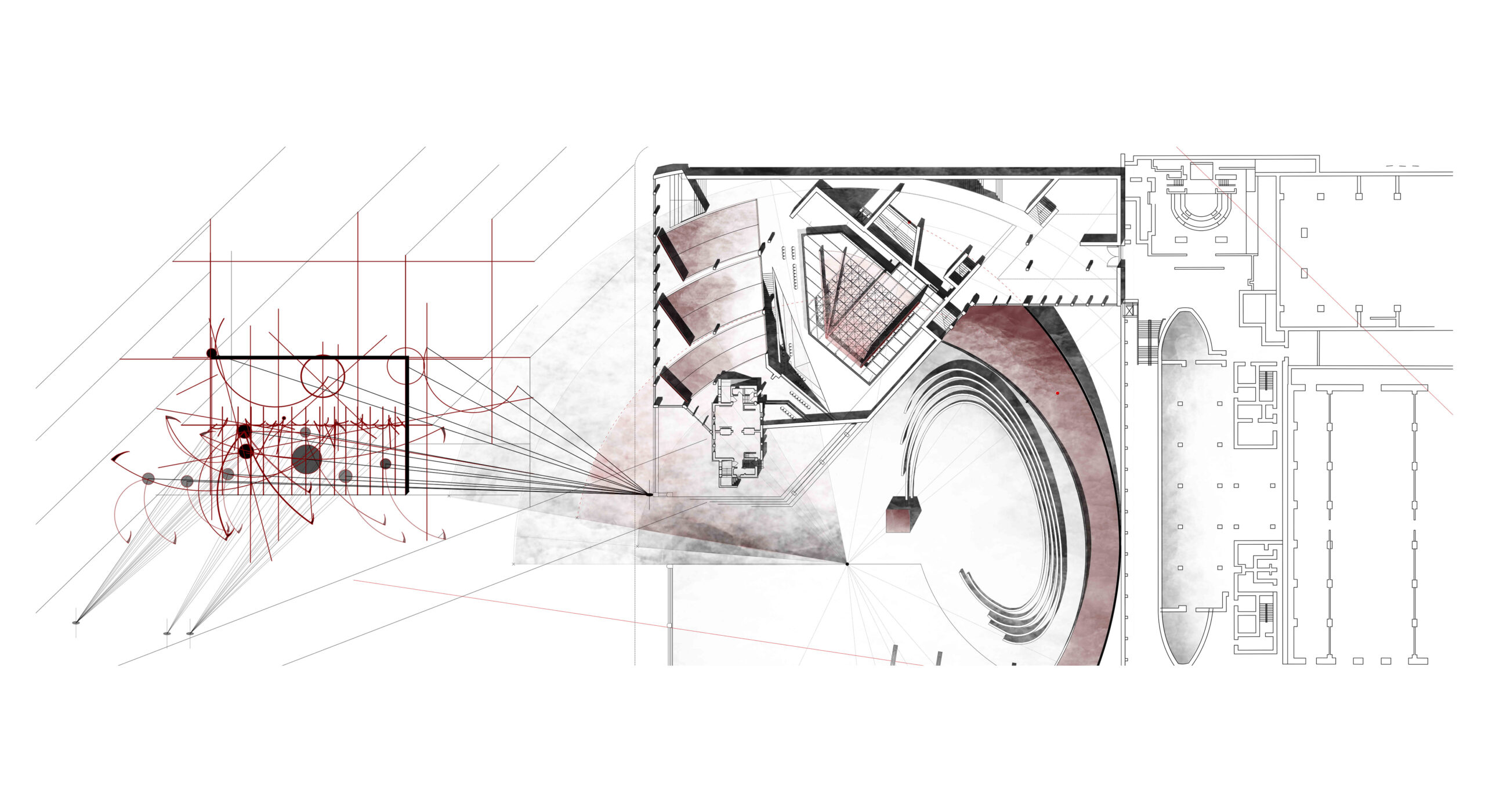

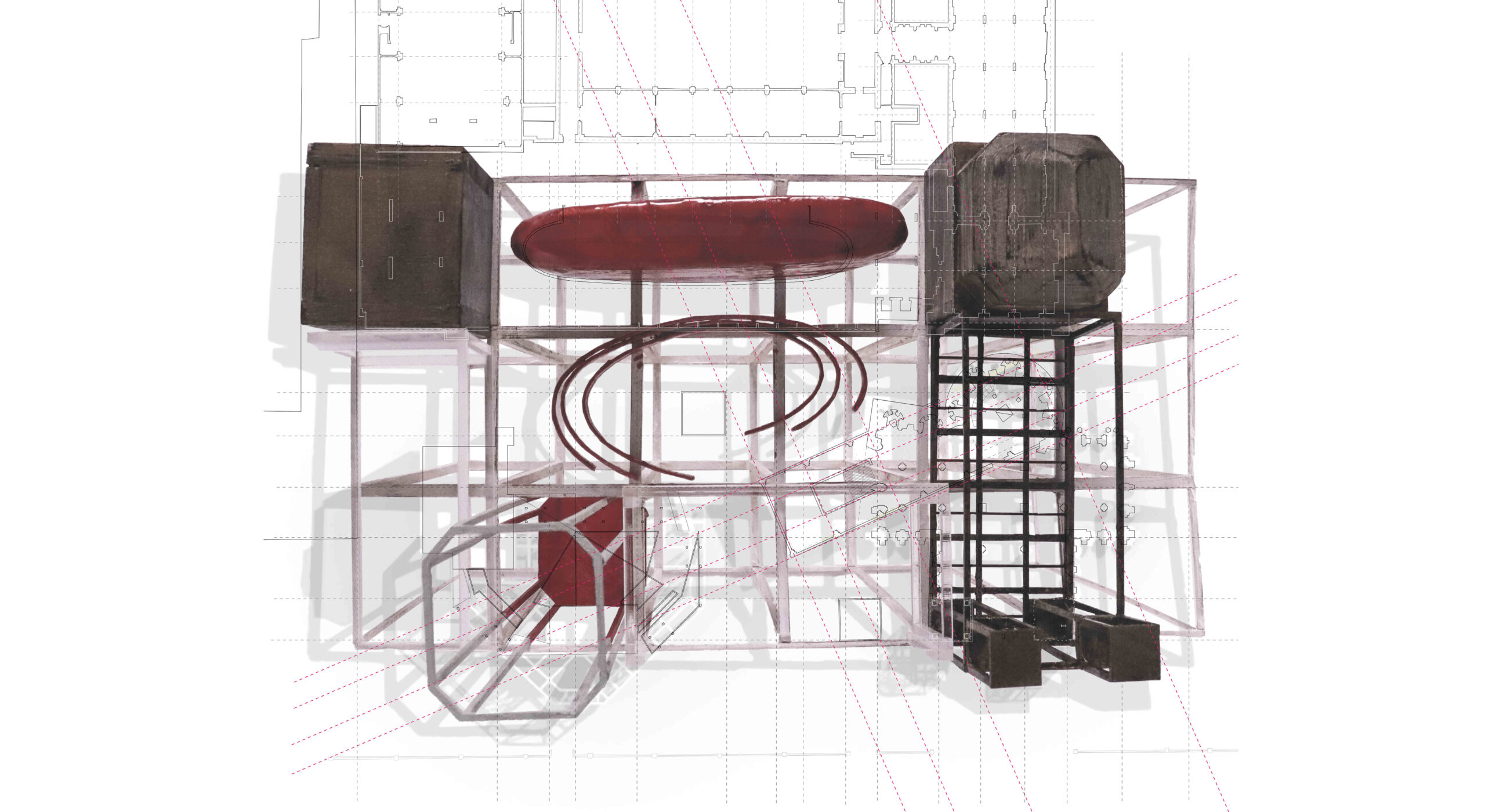

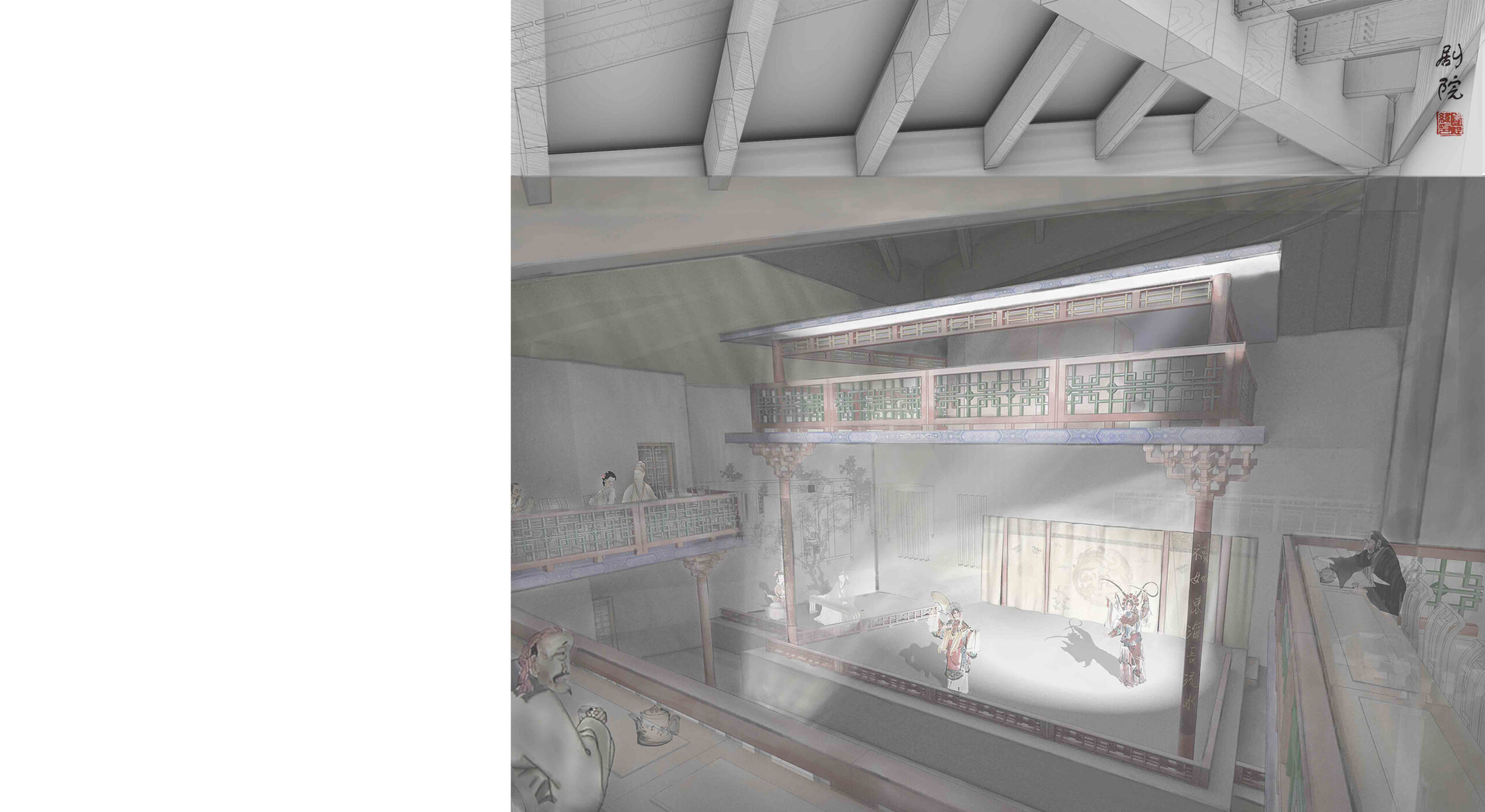

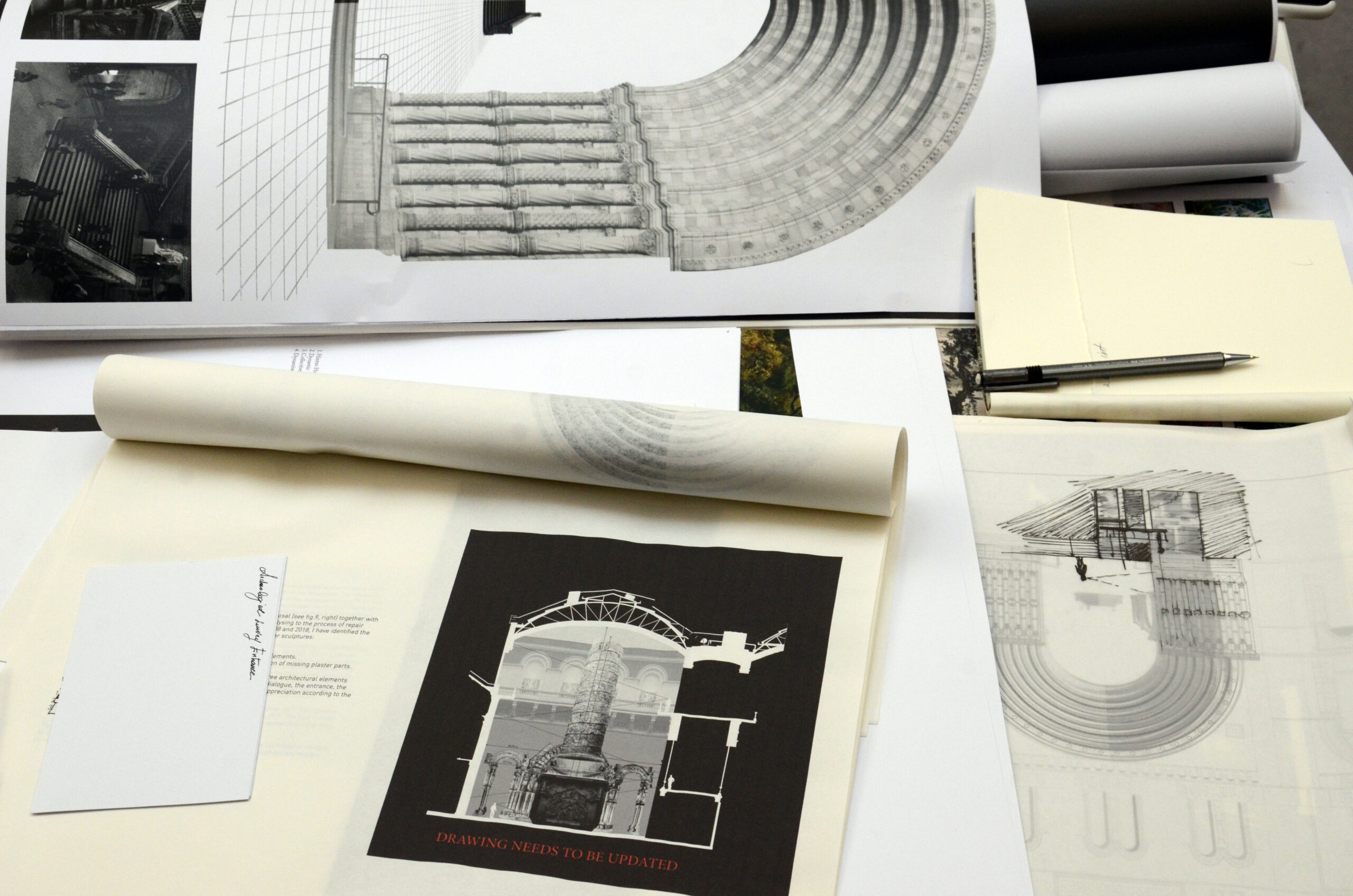

semester one: The Marianne North Salon

The Natural History Museum, London, and especially Alfred Waterhouse’s 1881 building is also referred to as ‘A Cathedral of Nature’.[5] The Museum formed part of a masterplan of education and cultural sites and this idea concerning the study of nature and natural history through observation not only acknowledged nature as an entity that can be displaced and contained, but (re)represented through paintings and drawings.[6] These new and different manners of presentation are especially evident in the botanical illustrations adorning the Hintze Hall.[7]

Similarly, the paintings of the nineteenth-century botanical artist and biologist Marianne North served as a global record of exotic plants during the Victorian era. Her scientifically accurate depictions of nature as occurring and including the immediate contexts were of biological importance at that time and led to many scientific discoveries.[8] These paintings are now exhibited in the Marianne North Gallery, 1882 in Kew Gardens, a building she bequeathed, oversaw the design for, and personally embellished. At present this space not only still contains the work of a single artist but more importantly, the paintings have remained in their original positions since the Gallery was conceived.

A select collection of North’s paintings will be bequeathed to the Natural History Museum, and a salon is deemed the most appropriate type of space to accommodate the works.[9] Through ongoing discussions, new arrangements and exhibitions the idea of nature as a static narrative, represented in a fixed manner is challenged. The new architecture celebrates the imaginative dialogue of the paintings, embodies North’s innovative spirit and serves to reflect upon the validity of this approach to the study of natural history.

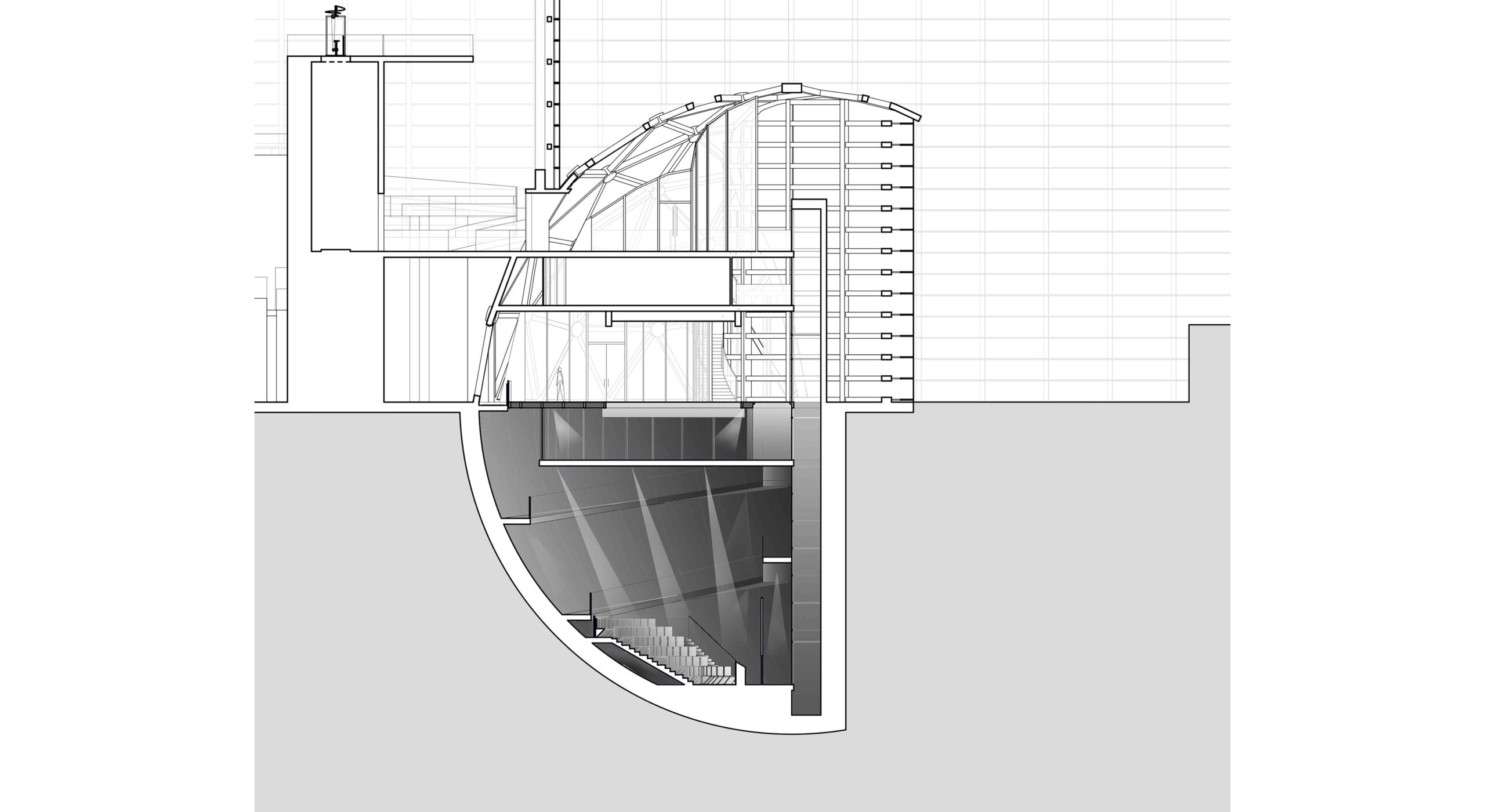

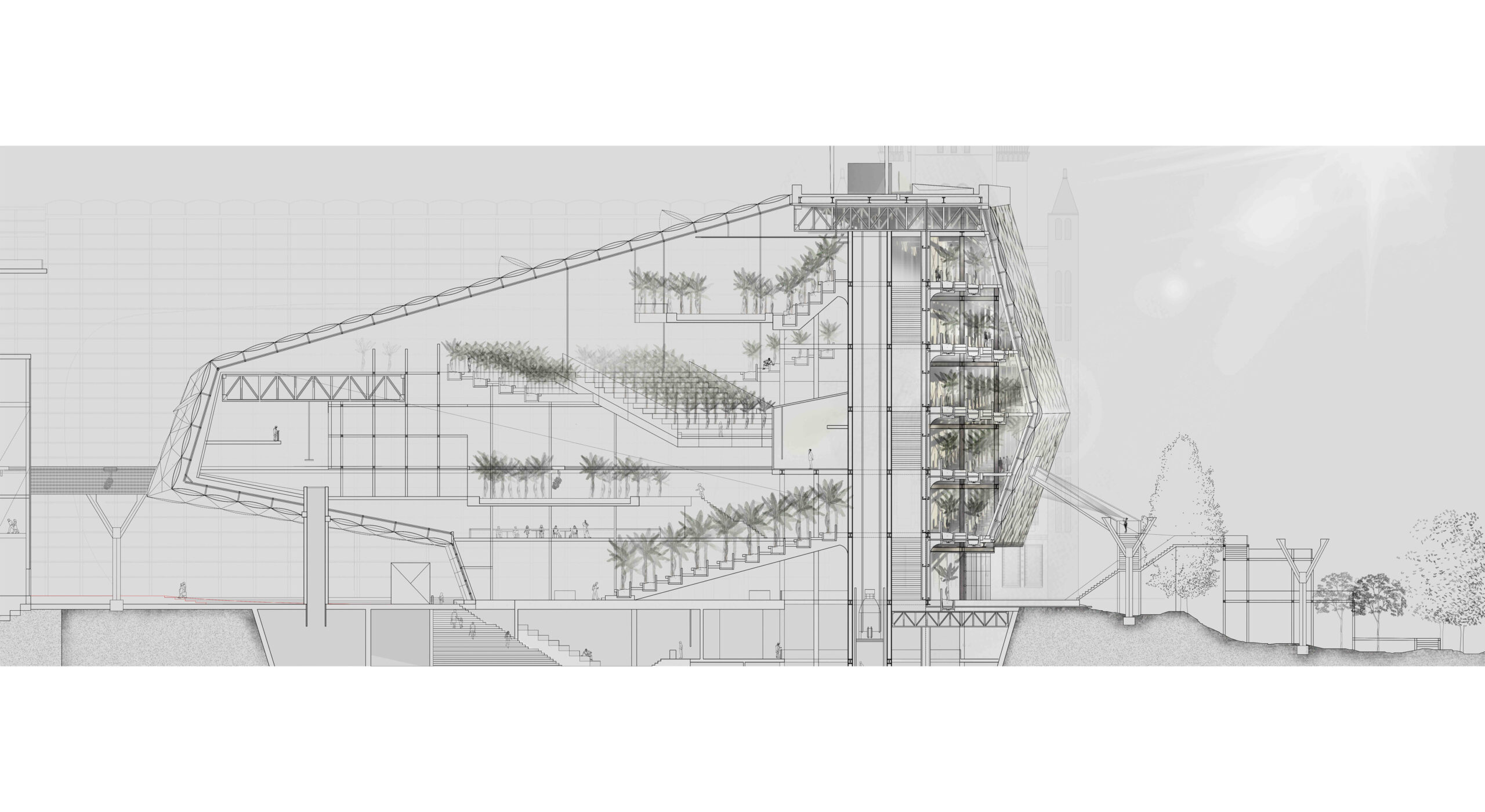

semester two: The Urban Pleasure Garden

While nature and ideas concerning natural history were mainly approached as displaced exhibits previously, the architectural proposals in semester 2 will explore nature as nature intended, through acknowledging site-specific weather conditions in addition to the historical boundaries of Waterhouse’s building, as well as the implications and allusions to Albertopolis.

1The idea of a gallery or museum as a leisure space as opposed to a learning and teaching space has been raised by Walter Benjamin who ‘saw the art museum in the mid-nineteenth century as simply one of many dream spaces, experienced and traversed by an observer no differently from arcades, botanical gardens, wax museums, casinos, railway stations and department stores’.[10]

The definition of leisure as an organized establishment was suitably reflected in the eighteenth-century Pleasure Gardens which were exquisitely landscaped parks where different and far-ranging forms of activities from theatres, operas, rides to menageries were available for purposes of entertainment and social interaction. More importantly, these places also served as showcases for the latest innovations in art and architecture.[11] Hence the user experience resulting from this cluster of seemingly unrelated activities with different visual and tactile boundaries contained within a said enclosure is of key interest and the notion of perambulation will be furthered to include vertical movement in this instance.

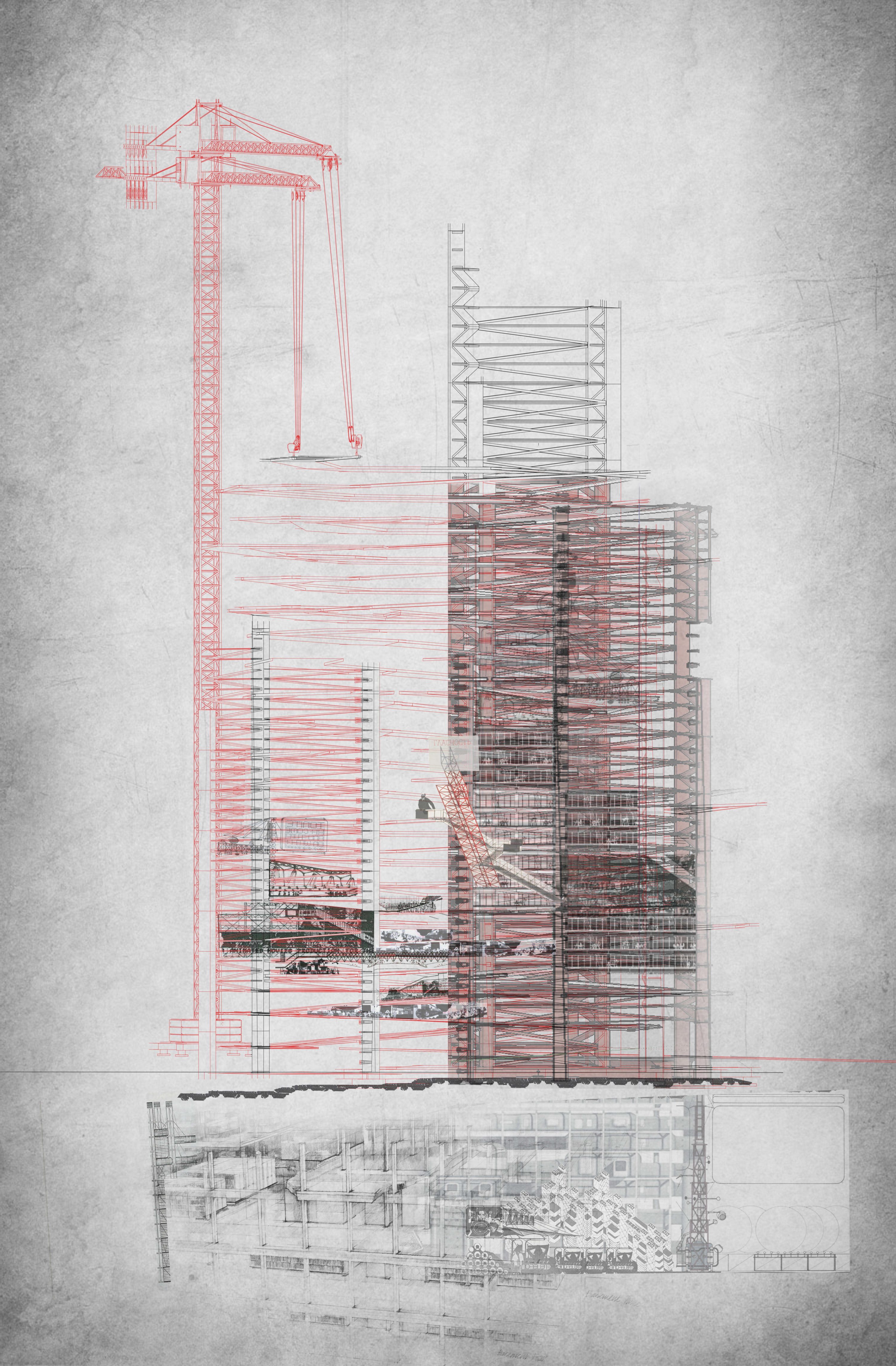

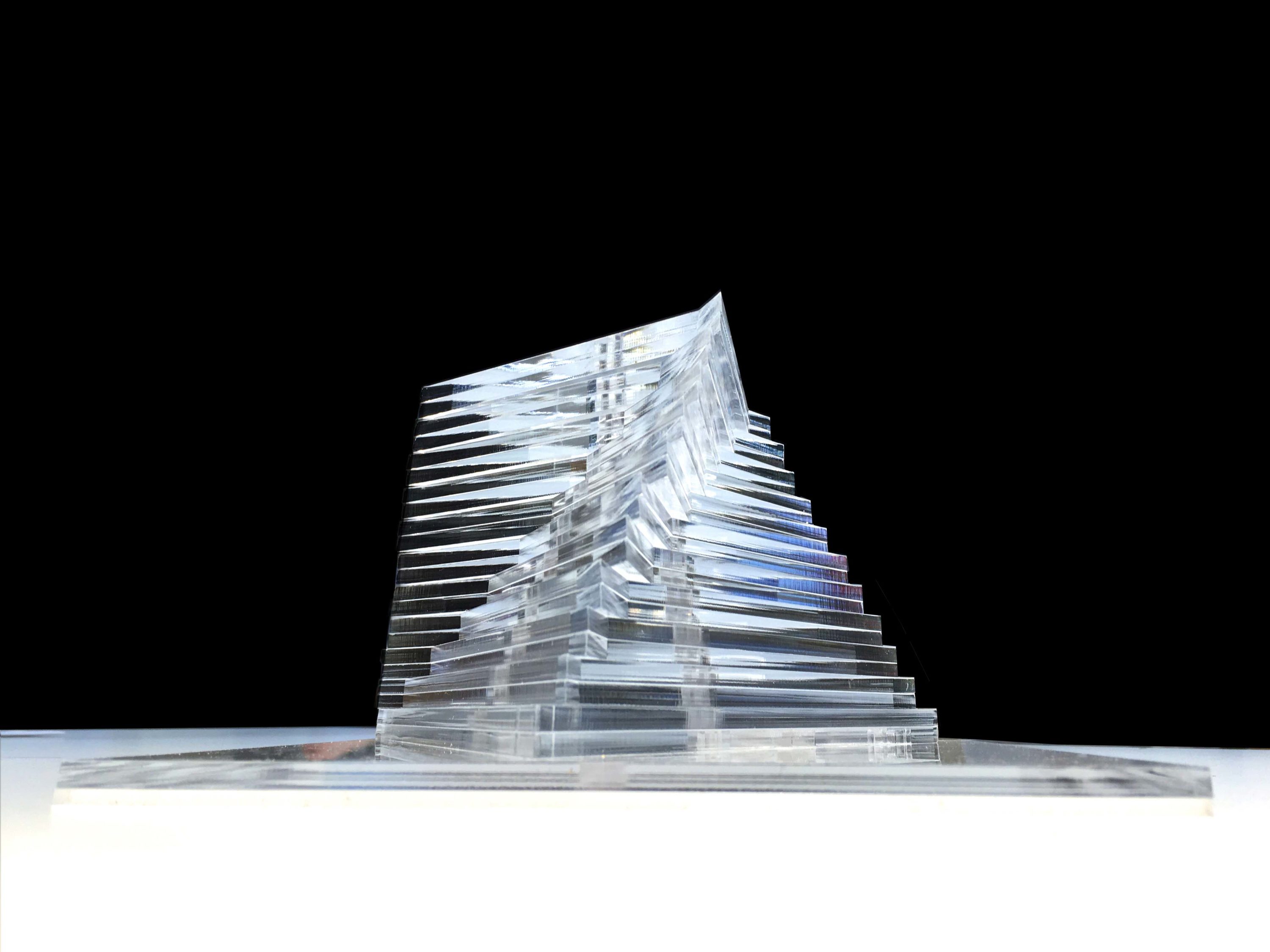

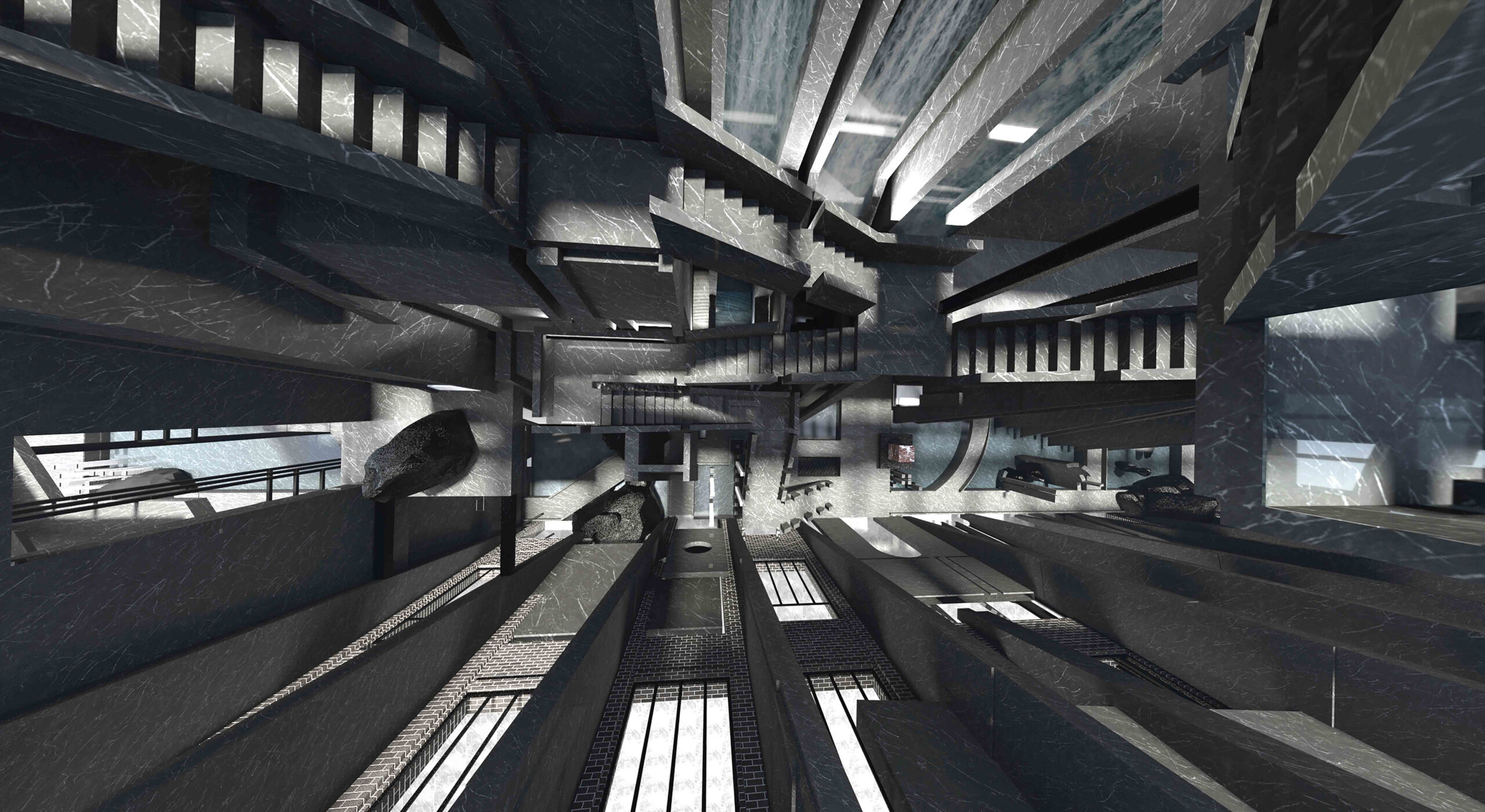

The architectural design

proposal for an Urban Pleasure Garden will

occupy the current phase I site of the Darwin Centre, inclusive of the Tsunami

Memorial courtyard. This vertical iteration will encompass existing functions

interwoven among new facilities to generate new user and spatial configurations

that are deemed appropriate for an Urban Pleasure Garden in this century. Once

again, the techniques of montage as a spatial device, ideas concerning the

picturesque where landscape and building(s)

are co-dependent, as well as critical arguments raised in The Manhattan

Transcripts will be appropriated for

the design proposal in this particular urban context. Hence your architectural explorations and spatial

manifestations concerning ‘sweet disorder and the carefully careless’ will response

to the public and private user, accommodate round the clock activities and most

importantly, contribute a modern architectural definition of nature and/or

natural history through issues of site, authorship, conservation and

presentation of the subject matter. Exploring notions of site,

science-fiction and sustainability, the translation of research material into

architecture encourages history to be (re)presented and take on its own

relevance in this present day.

[1] The fulfilment of the desire to ‘chart and to collect’ was in many parts due to the ‘vastness and diversity of the colonial realm.’ Darran Andersen, ‘The Men of a Million Lies, or How We Imagine the World’, in Imaginary Cities (London: Influx Press, 2015), p. 26. Also refer to the ‘Imperial Federation Map of the World’ showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886. Lastly, the Palm and Temperate Houses in Kew Gardens are good examples of the points being made in this instance.

[2] The advent and initial discussions concerning the picturesque is credited to William Gilpin. This movement in part challenged the ideologies of the established Grand Tour that prioritised symmetry and perfect proportions. Celebrated painters of this movement include Claude Lorraine and Gaspard Poussin.

[3] This concept is succinctly described in Eisenstein’s ‘Montage and Architecture’, by means of Auguste Choisy’s Histoire de l’Architecture, 1899, discussion concerning the buildings of the Acropolis, pp. 117-121.

[4] Also refer to Rousham gardens, designed by William Kent in the eighteenth-century.

[5] The ecclesiastical reference appeared again in Thomas Heatherwick’s ‘Seed Cathedral’, commissioned as the British pavilion for the 2010 Shanghai EXPO. The two phased Darwin Centre was added to the Museum in 2002 and 2009.

[6] The 1850 masterplan was also referred to as ‘Albertopolis’.

[7] With regards to discussions concerning narrative, presentation and assimilation, the information in the Hintze Hall has been further updated to reflect the current possibilities as afforded by this digital age. <https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/ZgIC0U5-YXGjLg> [assessed 20 August 2019].

[8] This was prior to the introduction of photographic documentation. It is also worth noting that North’s depictions were from the colonial viewpoint of a privileged viewer.

[9] This is historically a place where people congregated for intellectual discourse, and the commonly assumed aesthetics of walls lined with artworks for academic competitions comes from the nineteenth-century. Also refer to Sergei Shchukin’s Pink Drawing Room and/or Matisse Room in Moscow, Russia.

[10] Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995. First published in 1992) p. 23. The original source is noted as ‘Walter Benjamin, Das Passagen-Werk, vol. 1 (Frankfurt, 1982), pp. 510-523’.

[11] The earliest Pleasure Gardens are dated approximately 4000 B.C., but the most well known in London were Vauxhall, 1729-1858 and Ranelaugh, 1742, the latter is currently the site for the annual Chelsea Flower show.

Bibliography

BBC Documentary 2016, ‘Kew’s Forgotten Queen’ <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Z0CTSDUqvk> [accessed 19 August 2019].

Desmond, Ray, The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (London: Kew Publishing, 2007). First published in 1995.

Eisenstein, Sergei, ‘Montage and Architecture’, Assemblage 10, pp. 110-131.

Girouard, Mark, Alfred Waterhouse and The Natural History Museum (London: The Natural History Museum, 2009). First published in 1981.

Hill, Jonathan, ‘Architects of Fact and Fiction’, ARQ, vol., 19, no. 3, 2015, pp. 249-258.

Maxwell, Robert, Sweet Disorder and the Carefully Careless: Theory and Criticism in Architecture (New Jersey: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993).

Payne, Michelle, Marianne North, A Very Intrepid Painter (London: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2011).

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Marianne North: The Kew Collection (London: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2018).

Tschumi, Bernard, The Manhattan Transcripts (London: Academy Editions Ltd., 1981). Also refer to the summary on <http://www.tschumi.com/projects/18/> [accessed 19 August 2019].

Tschumi, Bernard, Architecture and Disjunction (Cam. Mass.: MIT Press, 1996).